Introduction

The Automated Valuation Model (AVM) industry is entering a critical phase—one where regulatory oversight is increasing, use cases are expanding, and performance analysis is under sharper scrutiny. In this environment, testing methodologies must evolve to ensure transparency, fairness, and real-world relevance. A recent whitepaper from Veros Real Estate Solutions, “Optimizing AVM Testing Methodologies,” advocates flawed logic that risks reversing progress in predictive model testing and validation.

This op-ed offers an affirmation of the core tenets of what is becoming the industry-standard testing framework: a data-driven testing methodology grounded in sound and prudent validation principles. While Veros challenges this approach, the broader AVM ecosystem—including regulators, lenders, and nearly all major AVM providers—have embraced a process that prioritizes objective, real-world performance measurements over now antiquated methods allowing for data leakage into the Automated Valuation Model.

The Listing Price Issue

The whitepaper in question should be understood as a salvo in the battle over listing prices and their influence on AVMs. Several industry participants have come out with analyses showing that when AVMs incorporate listing price data into their models, they perform much better in tests, but those test results are likely to be a poor reflection of real-world model performance. This is because in most use cases for AVMs, there is no listing price available – think of refinance and HELOC transactions, portfolio risk analyses or marketing (See AV Metrics August 29, 2024 whitepaper[1] or the AEI Housing Center’s Study of AVM Providers[2]).

Specific Issues in Veros’ “Optimizing…”

Below are seven points made in the aforementioned paper that don’t stand up to scrutiny. Let’s break them down one at a time.

- Mischaracterization of the Listing Price Concern

Whitepaper Claim: “Knowing the list price doesn’t necessarily equate to knowing the final sale price.” The paper not only puts forward the strawman that others claim that listing prices are equal to sales prices, but it also rather awkwardly asserts that listing prices are not very useful to AVMs

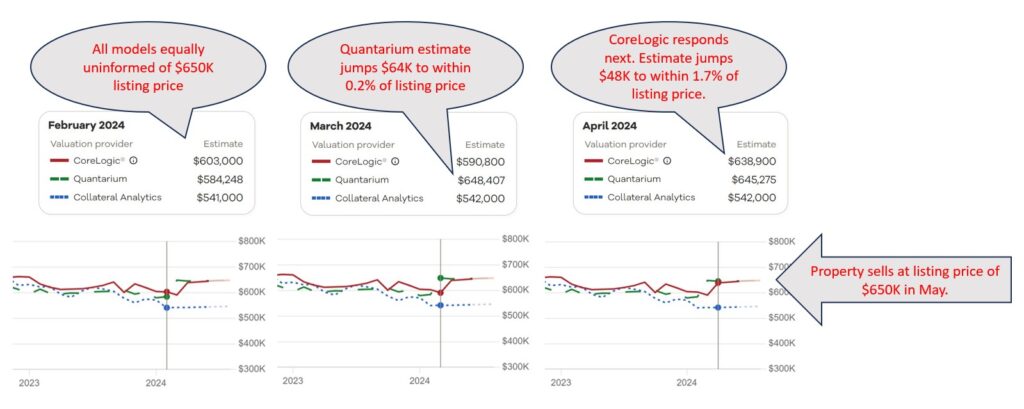

Response: This argument overlooks a key behavioral phenomenon: anchoring. When listing prices are published, they tend to drive sale prices and valuations toward that price[3]. When listing prices become available to AVMs during testing, model outputs shift—often sharply—toward those prices. Look no further than one of the most prominent AVMs on the market, Zillow. They are a very transparent company and publish their accuracy statistics monthly, and when they do, they measure them with and without listing data available, because the accuracy results are strikingly different. As of August 2025, Zillow’s self-reported median error rate is 1.8% when listing prices are available and 7.0% when they are not.[4]

AEI noted this phenomenon in their recent analysis of multiple AVMs from 2024, “Results on the AEI Housing Center’s Evaluation of AVM Providers[5].” AEI referred to it as “springiness” because graphs of price estimates “spring” to the listing price when that data becomes available. The result is inflated performance metrics that don’t reflect true, unassisted, predictive ability. And finally, this issue has been empirically documented in AV Metrics’ internal studies and external publications.

When AVMs are tested with access to listing prices, vendors can tune their models to excel under known test conditions rather than perform reliably across real-world scenarios. This undermines model governance, especially for regulated entities, and conflicts with both OCC and IAEG guidance emphasizing model transparency, durability, and independence.

The solution being adopted as the emerging standard is simple but powerful: only use valuations generated before the listing price becomes known. This ensures unanchored estimates using real-world scenarios where listing prices are unavailable—a more accurate reflection of likely outcomes for use cases such as refinance, home equity, and portfolio surveillance.

- Refinance Testing and the Fallacy of Appraisal Benchmarks

Whitepaper Claim: “Appraised values are the best (and often only) choice of benchmarks in this lending space currently as they are the default valuation approach used to make these lending decisions.”

Response: Appraisals are opinion-based and highly variable. In fact, Veros’ own white paper acknowledges that appraisals exhibit high variance, a concession that undermines their validity as testing benchmarks. Appraisal opinions are not standardized enough to provide consistent benchmarks as a measure for AVM accuracy.

Closed sale prices offer a clean, objective benchmark. If the aim is to measure how well an AVM, or other valuation method, predicts market value, then only the actual transaction data meets that standard. AV Metrics published an explanation of the superiority of sales prices over appraised values in May of 2025[6].

Regulatory guidance also emphasizes the superiority of transactions over appraisals for AVM testing. Appendix B of the Interagency Appraisal and Evaluation guidance, December, 2010[7], still the most current guidance of AVM testing, specifically states, “To ensure unbiased test results, an institution should compare the results of an AVM to actual sales data in a specified trade area or market prior to the information being available to the model.”

- Mischaracterization of Pre-Listing Valuations as “Outdated”

Whitepaper Claim: The whitepaper asserts that validation results using pre-listing AVM values are artificially low, asserting that these values are outdated and fail to reflect current market conditions. While Veros stops short of using the phrase “outdated and unfair,” that is the unmistakable thrust of their argument: that pre-listing AVM estimates do not reflect real-world usage and disadvantage high-performing models. In the webinar discussion of the whitepaper, Veros repeatedly suggested that “Pre-MLS” testing might use AVM value estimates that were 9 months old.

Response:

This claim is both overstated and analytically misleading.

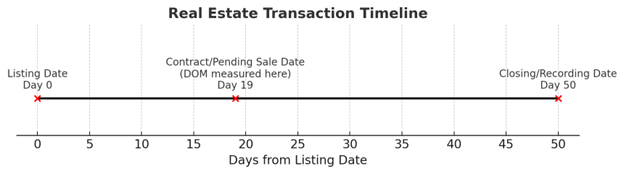

PTM testing never uses values that are 9 months old, and industry participants know that, because they are familiar with the methodology and AV Metrics’ paper describing it[8]. The reality is that almost all AVM values used in PTM testing were created mere weeks or a month or two prior to the relevant date, which is the contract date. The Veros paper uses confusion over different dates in the process of a real estate transaction to muddy the waters. The timeline below shows how the “median DOM” referred to in the paper and commonly published in business articles is not representative.

In the real estate industry, Days on Market (DOM) is often defined as the number of days from Listing Date to Closing/Recording Date. Sources like FRED and Realtor.com report median DOM this way, which for April 2025 was about 50 days.

However, for valuation relevance, the more important measure is the time from Listing Date to Contract/Pending Sale Date—the point when the actual price agreement is made. This is typically much shorter—our April 2025 Zillow data show a median of 19 days nationally.

This matters because AVM predictions made just before the listing date are often only weeks ahead of the market decision point, not months. By contrast, the “closing” date used in some public stats is just a paperwork formality that lags well behind the actual market valuation event.

Furthermore, residential real estate markets do not shift dramatically week to week. The suggestion that valuations generated days or a few weeks prior to the listing date are best characterized as outdated misunderstands the pace of market change and misrepresents the data.

Using pre-listing AVM values does not disadvantage models, nor are those values meaningfully outdated. On the contrary, PTM removes a long-standing bias—early access to listing prices—and holds all AVMs to the same fair standard. The result is a more objective, transparent, and predictive test that rewards modeling performance rather than data timing advantage.

Key Points:

- Veros’ “9 months” claim is unrealistic—typical contract timing is closer to 2–4 weeks after listing.

- Residential markets move slowly: 1–2% change over several months, often less.

- Any slight “age” in pre-listing AVM estimates is minimal, consistent across all models, and far outweighed by the benefit of removing listing price bias.

When tested properly, AVMs show robust performance even when limited to pre-listing data, proving that predictive strength—not access to post-listing artifacts—is the proper basis for fair evaluation.

- The Flawed Analogy to Appraisers

Whitepaper Claim (Paraphrased): Veros argues that AVMs should be allowed to use listing data in testing because appraisers do. The whitepaper pleads for AVMs to be allowed to operate like appraisers with access to listing data in order to compete with appraisers on a level playing field.

Response: This argument confuses different points. First, appraisers and AVMs are not equals competing on a level playing field. They are different processes for estimating market value. Appraisers are held to standards to develop and report appraisal estimates by the Uniform Standards of Professional Appraisal Practice. These types of standards are non-existent for AVMs. Perhaps to counter the lack of standards at the manufacturing end of the AVM estimates, model estimates are tested on the backend to evaluate accuracy and meet regulatory expectations. Appraisers aren’t subjected to the rigorous testing that AVMs go through, though appraisal users typically have review processes in place at both the transactional and portfolio levels.

Second, there are several different “uses of appraisal data” being conflated in this claim. AVMs are able to use many different types of data from listings in their models without objection. They often ingest pictures and text descriptions and they’ve developed very sophisticated AI techniques to tease out information from those descriptions.

But there is one specific issue under debate, and that is the use of the listing price information when AVMs are being tested. Users of AVMs need to understand how accurate a model will be when listing data is not available, as it is not available in most AVM use applications: e.g. refinances, HELOCs, portfolio valuation and risk assessment, etc. For testing to be most applicable to those situations and uses, AVM testing must be done on value estimates not “anchored” to listing prices.

AVMs are evaluated by statistical comparison to a benchmark. Injecting listing prices into the models contaminates the experiment, especially when that price closely tracks the final sale. Appraisers aren’t ranked side by side using controlled benchmarks. That difference is why AVMs should not be tested with access to listing prices, but they certainly should be able to use listing data.

- False Equivalency with Assessed Values

Whitepaper Claim: “If we eliminate the use of MLS list prices, should we also argue for excluding other potentially useful data, such as that from a county property tax assessor?” The paper claims that other estimates of value available in the marketplace are not excluded by PTM testing, so it asks why listing prices should be singled out for exclusion.

Response: This argument is a strawman set up to be knocked down easily. Assessed values are stale and generally unrelated to current market value. They also tend to cover every property, meaning that they don’t privilege the small percentage of properties that will be used as benchmarks, thereby invalidating accuracy testing. But, most importantly, they do not create the same anchoring distortion that listing prices do. For these reasons, no one has suggested excluding assessor values, because it wouldn’t make sense. Later in the whitepaper, they answer their own rhetorical question by saying that it is “absurd” to consider eliminating access to assessor data. We wholeheartedly agree. It was, in fact, absurd to even suggest it.

- Alternative Proposal: Measure Anchoring

Whitepaper Suggestion: The paper proposes using some statistical techniques to measure the amount that each AVM adjusts in response to listing prices.

Response: This suggestion is interesting for exploratory research, but it is not a viable alternative. It fails to address the basic question: how well does this model predict value when no listing price is available? The Predictive Testing Methodology (PTM) answers that question in a scalable, repeatable, and unbiased way. Simply calculating how much an AVM responds to listing prices does not accomplish that goal.

- The Flaws of “Loan Application Testing”

Whitepaper Proposal: Veros suggests a new AVM testing approach based on pulling values at the time of loan application—arguing that this better reflects how AVMs are used in production, especially in purchase and refinance transactions.

Response: While this may sound pragmatic, in practice, “loan application testing” is deeply flawed as a validation methodology. It introduces bias, undermines statistical validity, and fails to meet regulatory expectations for model risk governance. Here’s why:

- Not Anchoring-Proof

If an AVM runs after the property is listed (as many do at loan application), it may already have ingested the list price or be influenced by it. This reintroduces anchoring bias—precisely what PTM is designed to eliminate. - Biased Sample and Survivorship Distortion

Loan applications represent a non-random, self-selecting subset of properties. They exclude properties for which there is no loan application (about 1/3 of all sales are for cash and don’t involve a loan) as well as those that are quickly denied, withdrawn, or canceled. This sampling would severely bias testing. - Inappropriate Appraisal Benchmarks

The mix of AVM testing benchmarks would vacillate between appraisals for refinance loan applications and sales for purchase applications. Depending on market conditions, refinance applications can make up 80+% of loan originations, which would mean that the vast majority of AVM testing would be based on appraisals, which are subjective and inappropriate as a benchmark. - Non-Standardized Collection & Timing

There is no consistent, auditable national timestamp for “application date” across lenders. This creates operational inconsistency, poor reproducibility, and potential for cherry-picking.

Veros’ proposal is not a viable alternative to PTM. It lacks the rigor, scalability, and objectivity that predictive testing delivers—and it would fall short of the new federal Quality Control Standards requiring random sampling, conflict-free execution, and protections against data manipulation.

About the Author and the Need for Independent Testing

It is also important to acknowledge that the Veros whitepaper was authored by a model vendor—evaluating methodologies that directly affect its own model’s competitive standing. This is not an independent or objective critique. Veros is an active participant in the AVM space with commercial interests tied to model performance rankings. By contrast, Predictive Testing Methodology (PTM) is conducted by an independent third party, is openly adopted by nearly all major AVM vendors, and has become a trusted standard among lenders seeking impartial performance assessment.

Conclusion: Clarity Over Convenience

At its core, AVM testing is about one thing: accurately establishing an expectation of a model’s ability to predict the most probable sale price of a property. To achieve this, we must rely on objective benchmarks, control for data contamination, and apply consistent standards across models.

The Predictive Testing Methodology (PTM)—already adopted by nearly all major AVM providers—meets these criteria. It has been embraced by lenders and validated through years of use and peer-reviewed research. Anchored in OCC 2011-12 model validation guidance, IAEG principles, and the newly codified 2024 Final Rule on AVM Quality Control Standards, PTM ensures that AVMs are tested as they are used—in real-world, data-constrained conditions. These new federal standards require AVM quality control programs to:

- Protect against data manipulation, such as anchoring to listing prices;

- Avoid conflicts of interest, emphasizing the importance of independent testing providers;

- Conduct random sample testing and reviews, ruling out cherry-picked case studies or selectively favorable data;

- And comply with fair lending laws, requiring AVM frameworks to be broadly equitable and empirically validated.

Veros’ whitepaper makes the case for less rigorous framework. But flimsy frameworks serve vendors, not users, and especially not regulated users. They inflate performance, mask limitations, and misguide deployment. The industry would do well to resist this regression as such approaches would fall short of the standards now required by law.

The industry should reaffirm our commitment to testing that is transparent, unbiased, and fit for purpose. That is how to build AVM systems worthy of trust and meet both the expectations of regulators and the needs of a fair, stable housing finance system.

AV Metrics is an independent AVM testing firm specializing in performance analytics, regulatory compliance, and model risk management.

[1] https://www.avmetrics.net/2024/08/29/avmmethodologytestingstudy-2/

[2] https://www.aei.org/research-products/report/results-on-the-aei-housing-centers-evaluation-of-avm-providers/

[3] Systemic Risks in Residential Property Valuations Perceptions and Reality. June 2005 from CATC… “Full Appraisal Bias” –Purchase Transactions page 13

[4] See https://www.zillow.com/z/zestimate/

[5] https://www.aei.org/research-products/report/results-on-the-aei-housing-centers-evaluation-of-avm-providers/

[6] https://www.avmetrics.net/2025/05/01/appraisals-are-not-appropriate-for-testing-avms/

[7] https://www.fdic.gov/news/news/financial/2010/fil10082a.pdf

[8] https://www.avmetrics.net/2024/08/29/avmmethodologytestingstudy-2/